The African Oystercatcher Haematopus moquini is one of the iconic species of the coastline of the southwestern Africa. There is only one oystercatcher that breeds exclusively in Africa. So the “black” in African Black Oystercatcher is redundant, and is in the process of being dropped, in favour of the shorter name!

Identification

African Oystercatchers, especially the adults, are one of the easiest bird species to identify. It is the only species along the African coast with a black body and a bright red bill. They are noisy birds; listen to them here.

Young African Oystercatchers are duller than adults. The most conspicuous differences are the bill colour, the lack of an eye ring, and the leg colour. The plumage is a dull brownish black, rather than plain black!

Habitat

African Oystercatchers are essentially confined to the shoreline. They occur on both rocky and sandy shores. They tend to be most abundant on shorelines which are sheltered, they are rarer on exposed shores, and absent from sections of coastlines where the ocean’s waves pound directly onto the bases of cliffs. On rocky shores, their daily cycles are driven by the tide. They feed in the intertidal zone at low tide, and loaf on rocks at high tide, often getting together in roosting groups. They feed at low tides during the night as well as during the day.

Distribution

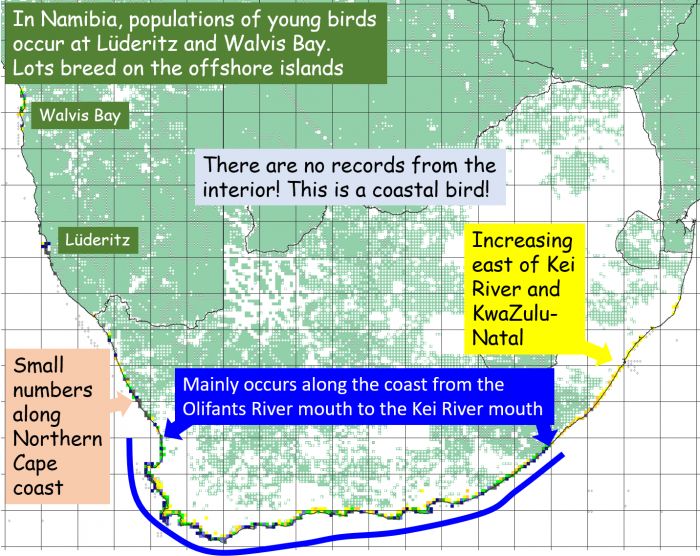

This is the SABAP2 distribution map for the African Oystercatcher. It occurs only along the coastline. In reality, the width of the distribution is even narrower than that shown on the map. In most places the strip of coastline in which you can find oystercatchers is about 50 m wide, from the lowest level of spring low tide, to a few metres above the spring high tide level. It is steadily expanding its breeding range northeastwards across KwaZulu-Natal. Vagrants have been recorded along the Angolan coast in the west, and in Mozambique in the east.

Behaviour

African Oystercatchers are strongly territorial, and once they settle in a territory, they remain on it and defend it for the rest of the lives, up to 15 to 20 years. They are noisy birds, with lots of social interactions with their partners and their neighbours. Pairs do lots of ritualized ceremonies, as shown in the photo below.

Breeding

The breeding season of African Oystercatchers coincides with the midsummer holiday period; most eggs are laid from November to February in South Africa, and about two months later in Namibia. The nests are just above the spring high tide level; the incubation period is about 30 days, so nests need to be high enough up the shore to avoid being washed away by two sets of spring tides. The nests cannot be made too far up the shore, because this would place them in the vegetation, and make the incubating bird vulnerable to predation by, for example, a mongoose.

Whether they are breeding on a rocky shore or a sandy beach, oystercatchers don’t go to lot of trouble building nests. They have a minimalist approach to nest architecture! It is best described as a scrape, and is sometimes lined with some seashells. Here are three examples.

The next nest, on a sandy beach, is in the dead centre of the photo, and contains two eggs:

The nest has been placed in a bend in the kelp. There are small round stones scattered around, which look quite egg-like.

This “nest” illustrates the minimalist approach:

The parents take turns incubating the eggs. It is hard to believe how difficult it is to spot a black bird with a red dagger for a bill sitting on its eggs on a white sandy beach:

… if you need a clue, the bird is near the right edge of the photo, and it is looking at the camera! Here it is close up:

Ultimately, two spring tides later, the eggs hatch, and a fluffball emerges. The second egg is pipped and the chick will emerge soon. The fluffball has dried off since it hatched. It’s a bit of packaging miracle how it could have squashed into an egg an hour or two earlier:

The chicks leave the nest within about 24 hours. They move up and down the shore with their parents, in rhythm with the tides. They are fed small pieces of mussels and limpets. They start to fly at about 40 days, when they reach 2/3rds of the adult mass. They hang around with their parents until they are about 100 days old. It is only then that their bills are strong to be able to prize shellfish off the rocks and feed themselves. It is a big commitment being an oystercatcher parent.

This juvenile was newly fledged, and was still learning to fly. The bill has some growing to do to reach adult size! The adult has a ring, and was probably ringed on this same territory on Robben Island in 2021 or 2022. African Oystercatchers, once they acquired a breeding territory, live a long time.

African Oystercatcher Gallery

Occasionally, and this happens in most bird species, the colouring goes completely haywire, and you have no idea what you are looking at. Like the bird on the left, gosh!

Luckily, in this case, the aberrant bird is standing alongside an African Oystercatcher, so it is pretty obvious what it actually is. This bird did not produce normal amounts of melanin, the pigment that turns feathers black. So it ended up a motley brown. This condition is called leucism. (There is a section of the Virtual Museum that curates photographic records of Birds with Odd Plumage, BOP.)

If you are amazingly lucky you might encounter a flock of oystercatchers and have one that sticks out like a sore thumb. It clearly an oystercatcher, slightly smaller than the African Oystercatchers, but is white as well as black. It is clearly not a plumage aberration, it is too neatly patterned for that!

If you are in southern Africa, awesomely well done, you have found a vagrant, the Eurasian Oystercatcher Haematopus ostralegus. (If you are in Africa north of the equator, this is the only oystercatcher you will encounter.)

Further resources: A selection of papers and a video:

- Conservation Status of Oystercatchers Around the World (2014). Assessment of the Conservation Status of African Black Oystercatcher. Chapter in book published by the International Wader Study Group

- Video in the BDI YouTube channel (2021). African Oystercatchers on Robben Island

- Species text in the first bird atlas (1997). African Black Oystercatcher Haematopus moquini

- The journal Wader Study has an Open Access paper published in 2021: African Oystercatchers on Robben Island, South Africa: The 2019/2020 breeding season in its two decadal context

- The journal Biodiversity Observations has an Open Access paper describing how the range of the African Oystercatcher has changed between the first and second bird atlas projects (SABAP1 and SABAP2)

More common names: Swarttobie (Afrikaans), Huîtrier de Moquin (French), Kapausternfischer (German), Ostraceiro-preto (Portuguese), Ostrero Negro Africano (Spanish)

A list of bird species in this format is available here.

Recommended citation format: Underhill LG 2021. African Oystercatcher Haematopus moquini. Biodiversity and Development Institute. Available online at https://thebdi.org/2021/06/07/african-black-oystercatcher-haematopus-moquini/