Cover image of Southern Boubou by Pieter la Grange

The Southern Boubou belongs to the Bushshrike family MALACONOTIDAE. Other members of this group include Tchagra’s, Bushshrikes, Puffbacks, and Gonoleks. They are smallish passerine birds with robust bodies, strong legs and feet, and formidable shrike-like bills. Many are very colourful and most species are rather secretive. The majority occur in woodlands, but also in marshes, scrub and Afromontane or tropical forest. They were formerly classed with the true shrikes in the family Laniidae, but are now considered sufficiently distinctive to be separated from that group. The family is endemic to sub-Saharan Africa but is completely absent from Madagascar. The name Malaconotidae alludes to their fluffy back and rump feathers.

Identification

The Southern Boubou is a tri-coloured bushshrike with a distinctive call. It is sexually dimorphic, the sexes differ slightly in plumage colouration.

Photo by Gregg Darling

Adult males have glossy black upperparts, including the top and sides of the head, back, wings, and tail, with a conspicuous white stripe on the folded wing. The underwing coverts are cream coloured. The underparts, including the chin, throat and breast are white. The flanks are orange-yellow to rufous. The thighs and lower belly are rufous, turning rich cinnamon-rufous on the vent and lower flanks.

Photo by Janet du Plooy

Females are much like males but the forehead down to the mantle is dark grey and they have more extensively rufous underparts. In both sexes the bill is black and strong with a hooked tip, and the legs are dark grey. Males have black eyes while those of the female are brown. Juvenile birds resemble the adult female, but carry variable buff and dusky streaking above and their underparts are barred rufous.

Within its range the Southern Boubou is only likely to be mistaken for the Tropical Boubou (Laniarius major), but that species has pinkish (not rufous) underparts. The two species sometimes hybridise where their ranges meet in the Limpopo River valley.

Photo by Pieter Cronje

Status and Distribution

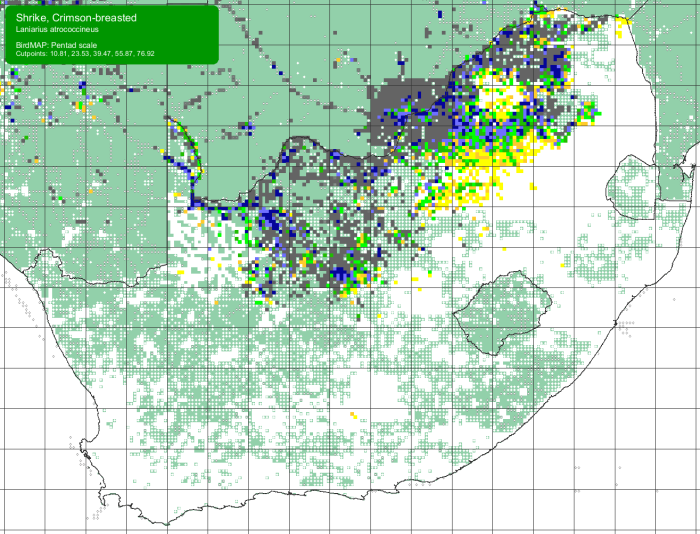

The Southern Boubou is a common to locally common resident. It is endemic to southern Africa and is confined to the moister eastern and southern parts. The Southern Boubou is found throughout southern Mozambique and very marginally in south-eastern Botswana and southern Zimbabwe. It is widespread in South Africa, occurring virtually throughout the northern, eastern and southern parts of the country.

Details for map interpretation can be found here.

The Southern Boubou is not threatened. There is no evidence to suggest that its distribution has changed much in recent times. However, the Southern BouBou is likely to have benefitted from the spread of alien scrub and thickets in some areas.

Photo by Andrew Hodgson

Habitat

The Southern Boubou inhabits the dense tangled undergrowth of most forest and woodland types in within its range, from sea level to high altitudes. It occupies montane forest, coastal forest and thicket, riverine forest and scrub, mangroves, gardens and alien plantations. In drier areas it is confined to thickets along watercourses. In open woodland and grassland habitats the Southern Boubou occurs in thickets and along drainage lines.

Shongweni Dam Nature Reserve, KwaZulu-Natal

Photo by Alex Briggs

Behaviour

The Southern Boubou is a resident and sedentary species throughout its range. Pairs appear to remain within the same territory for life. The Southern Boubou is mostly encountered singly or in pairs. They are rather secretive, scuttling through vegetation and the woody undergrowth of thickets.

Photo by Colin Summersgill

By virtue of its skulking habits, the Southern Boubou is more often heard than seen. Its calls are distinctive, far-carrying, and well known. The calls incorporate a varied repertoire of highly developed duets. The flight is heavy and slow, with shallow, rapid wing-beats.

Photo by Pamela Kleiman

They mainly search for food on the ground by hopping and leaf tossing, usually keeping to the shade under vegetation. They seldom move into the open. The Southern Boubou also forages on the lower branches and trunks in the under-story, investigating holes and pulling away bits of bark for prey. Also hawks flying insects on occasion.

Photo by Neels Putter

The Southern Boubou feeds mainly on insects like beetles, grasshoppers, caterpillars, wasps, bees, and ants. They are partial to snails, and also consume ticks, earthworms and other invertebrates. The Southern Boubou is known to eat small mice and reptiles such as geckos, as well as bird eggs and nestlings. Aloe nectar, small fruits, seeds and fresh shoots are also eaten in season. Around human habitation they will feed on scraps like discarded bread crumbs, grain and porridge.

Photo by Andrew Keys

Bee stings are rubbed off against a branch, and hairy caterpillars are vigorously rubbed against a branch or in sand before being eaten. Snail shells are broken open by repeatedly banging it against a branch. They may even wedge snails in a tree fork before tearing out the flesh. They also probably impale prey on thorns from time to time in the same manner as true shrikes (Lanius spp.), after all, the Boubou Genus Laniarius also means ‘butcher Bird’.

The Southern Boubou breeds from September to December in the north and east of its range. Breeding starts slightly earlier in the winter-rainfall region, from August to December.

The Southern Boubou is monogamous and pairs nest solitarily. They are territorial and will aggressively defend their territory, even plundering the nests of other species breeding close by.

Photo by Philip Nieuwoudt

The nest is an untidy, shallow bowl of roots, twigs and grass bound together with spider web. The female builds the nest by herself. It is usually well hidden in a dense bush, tree branch or creeper, rarely in an exposed, leafless fork. Most nests are located within 2m of the ground.

Photo by Daryl de Beer

2 to 3 eggs are laid per clutch. Eggs are pale greenish white, lightly speckled with browns and greys. The incubation period lasts for 16 or 17 days and is done by both sexes. Once the eggs hatch the eggshells are either eaten or carried away by the adults. Newly hatched young are altricial and are blind and naked. The nestlings faecal sacs are also either eaten or carried away. The nestling period takes around 17 days. Fledglings do not return to the nest but remain dependent on their parents for up to 8 weeks. The Southern Boubou is sometimes double-brooded.

The Southern Boubou is occasionally parasitised by the Black Cuckoo (Cuculus clamosus) and less often by Jacobin Cuckoo (Clamator jacobinus).

Photo by Gareth Yearsley

Further Resources

Species text in the first Southern African Bird Atlas Project (SABAP1), 1997.

The use of photographs by Alex Briggs, Andrew Hodgson, Andrew Keys, Colin Summersgill, Daryl de Beer, Gareth Yearsley, Gregg Darling, Janet du Plooy, Johan Heyns, Neels Putter, Pamela Kleiman, Philip Nieuwoudt, Pieter Cronje, and Pieter la Grange is acknowledged.

Virtual Museum (BirdPix > Search VM > By Scientific or Common Name).

Other common names: Suidelike waterfiskaal (Afrikaans); iBhoboni, iGqumusha (Zulu); Igqubusha (Xhosa); Gonolek boubou (French); Waterfiskaal (Dutch); Flötenwürger (German); Picanço-ferrugíneo (Portuguese).

List of bird species in this format is available here.

Recommended citation format: Tippett RM 2025. Southern Boubou Laniarius ferrugineus. Biodiversity and Development Institute. Available online at https://thebdi.org/2025/01/23/southern-boubou-laniarius-ferrugineus/

Photo by Johan Heyns