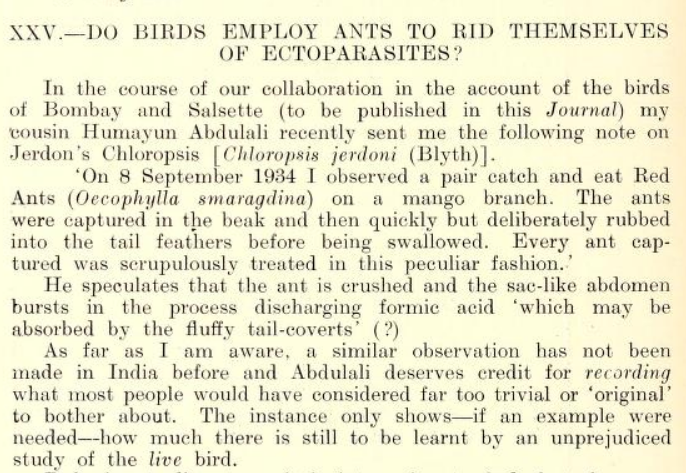

The term “anting” was invented in 1936 by the famous Indian ornithologist Salim Ali to describe a particular behaviour of birds. The first paragraphs of his paper are reproduced below. It provides a great example of citizen science!

In active anting, birds pick up ants in their bills, and rub them against their feathers and sometimes also their skin. In passive anting, the birds just lie down in a place where ants are abundant, such as an anthill, and allow the ants to crawl over them! They often then provoke the ants by rubbing their beaks close to them. The species of ant which are most commonly used for anting are those which produce formic acid. The formic acid, and the other chemicals produced by ants, put on the feathers might help birds to get rid of the various parasites and infections which negatively impact feather quality. For example, feather mites eat feathers, and any “remedy” for this would help survival and reproduction.

Unfortunately, the evidence in favour of this rather sensible hypothesis is not strong. Hannah Revis and Deborah Waller, in a paper in the journal Auk in 2004, did a series of experiments to try to show that anting reduced parasite loads, and found they did not. They concluded: “Our results, combined with those earlier accounts, support the importance of examining alternative hypotheses to explain anting behavior.” In other words, we don’t yet understand why birds “ant”. One alternative idea is based on the observation that birds mostly ant during moult, and that the behaviour is therefore performed to soothe skin which is irritated by the emergence of new feathers! Another idea, in a 1957 paper in the journal Wilson Bulletin, is a bit out of the box and largely discredited; it suggests that birds “appeared to derive sensual pleasure, possibly including sexual stimulation, from anting.”

A South African bird which does passive anting is the African Hoopoe. See the photo below!

Dieter Oschadleus, who leads BDI ringing events, has a website in which he describes anting in weavers. He has a list of 20 species of weavers But only five of them were recorded anting in the wild (the rest were in zoos). The five species are Cape Weaver, Village Weaver, Holub’s Golden Weaver, Southern Red Bishop and Red-billed Quelea. The ants used by these species were all in the subfamily Formicinae; all these ant species produce and store formic acid.

If you see birds anting, please take notes and photographs, and write a few paragraphs for Biodiversity Observations. Observing this behaviour is rare, or at least in Africa it is rare. For example, Eastern Cape ornithologist Jack Skead was a meticulous observer of bird behaviour over a period of 50 years of field work. He only once saw birds anting, and that was a Cape Weaver!