Lisl van Deventer has birded extensively at many exciting destinations. Before she travels, she invests a lot of time learning the key features of the birds she plans to see, and especially she tries to learn their calls. Here she is, armed with telescope and binoculars on a beach in Mozambique, close to Inhambane: “I ticked my Lesser Sand Plover lifer, in fact, there were gazillions of them amongst gazillions of other waders.” Photo credit: Anneke Vincent

BDI: Lisl, how did you become a citizen scientist? What was the catalyst that got you going?

Atlasing = Birding plus Numbers! I absolutely LOVE both!

BDI: What has been the highlight for you?

It has improved my birding skills. Because of the pentad system of the atlas atlas, I have visited off-the-beaten-track places in South Africa, seeing landscapes I would never have had a reason to go to.

BDI: How has being a citizen scientist changed your view of the world?

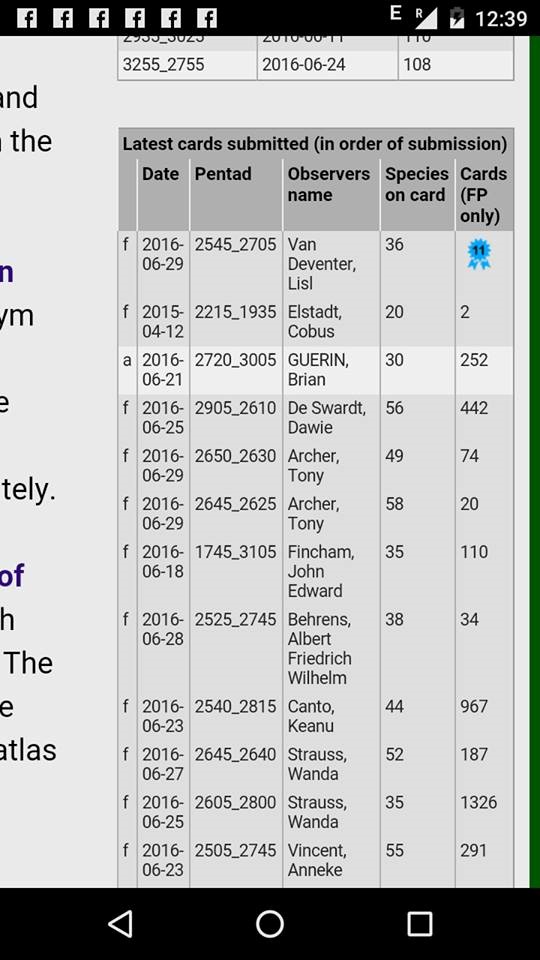

Meeting other atlasers and participating in the challenges (such as challenges in Greater Gauteng to turn all the pentads Green (7 checklists) and later on Blue (11 checklists)). Citizen science has taken me beyond my small world – you learn so much from other birders.

Atlasing in (poor) rural areas has been quite an eye-opener, and especially meeting some of the local people in these areas. They have a wealth of knowledge that is very useful for citizen scientists; sometimes it is simple information about the conditions of roads and at other times it is profound insights about the birds and how they are changing. It always amazes me how many locals can imitate bird calls and are curious to know the English bird names. Some locals understood details about the movement and migration of birds! It’s a huge pity some locals can’t be involved in citizen science to “tap” their knowledge. Sometimes one wishes that the voice recorder on the phone had been switched on to capture the insights. Many of these people lack their own transport and travel long distances to work means and have little time at home to do citizen science as we understand it.

BDI: What does the term “citizen scientist” mean to you?

Volunteers collecting and contributing data for research purposes.

BDI: What are you still hoping to achieve? This might be in terms of species, coverage, targets …

I am not focusing on atlasing at the moment, but rather using the knowledge that I’ve gained with the atlasing towards the BirdPix database. I am enjoying being part of the “expert panel” for BirdPix; sometimes it is a real puzzle to work out the species in the photograph.

BDI: What resources have been the most helpful? (And how can they be made better?)

BirdLasser has been awesome!! Would love to have the option of sorting the species alphabetically.

BDI: How do you react to the statement that “Being a citizen scientist is good for my health, both physical and mental!”?

Definitely! Atlasing is so rewarding! Being in nature reduces the work stress I’ve built up during the week, I get my dose of Vitamin D, it connects me with similar-minded people, mentally my thinking shifts beyond my little world to birding and to positive thinking (for example, I HAVE to find a House Sparrow for this pentad, I have to find five more species for this card).

BDI: What do you see as the role which citizen science plays in biodiversity conservation? What is the link?

Citizen science creates awareness, the volunteers spread the word and the public becomes aware and even involved. Data collecting provides an updated map of the distribution of a species, which revises knowledge about e.g. endangered species and in turn the focus of conservation can shift to those species. Volunteers assist by collecting and submitting data with their own finances and in turn saving money for the research project. With citizen scientist spread out in all corners of a country, the area of data collection spreads out as well and data can be collecting for species with a limited range.