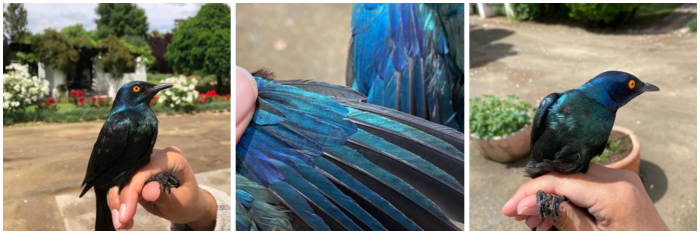

“Oh, it’s a glossy starling!” The car comes to a stop on the side of the highway. The passengers grab their binoculars and cameras and hop out of the vehicle, determined to get a closer look. New to the South African birding scene, I am not quite sure what I am looking for, but the team points my gaze in the right direction and suddenly I am acquainted with the Cape Glossy Starling for the first time. Its shimmering iridescent feathers, piercing yellow eyes, and regal appearance were a wonder to behold. We were about 40 minutes into our 700km drive from Vanrhynsdorp to Hanover. At first glance South Africa’s N10 Highway seems like it cuts through an endless, relatively homogenous, and languid landscape. After traveling caravan-style with a team of avid birders, I know for certain that this is not the case. I quickly learn to take in the scenery with an eye to the sky, ground, fences, and bushes; one can discover birds everywhere if they know to look for them.

This is how my week-long adventure in the Karoo—an expanse of semi-desert wilderness in South Africa’s Northern Cape—began. I was fortunate enough to be invited along on a citizen-science based bird ringing course offered by the Biodiversity & Development Institute and led by Dieter Oschadleus at the New Holme Lodge. I spent the week observing citizen science in action, learning about the region’s birds and biodiversity, and getting to know some remarkable, enthusiastic, and knowledgeable individuals.

The Karoo

The Karoo is a semi-desert region in Southern Africa. Its vegetation consists primarily of succulents, low shrub bushes, and grasses. The Karoo is widely devoid of surface water beyond small streams and constructed dams, explaining why it is known as the “land of thirst” in Khoisan. Despite its dryness, the Karoo is home to a vast array of birds and mammals, some of which we were acquainted with during our week at the KhoiSan Karoo Conservancy.

Some of the mammals we saw included:

- Aardvark

- Spring Hare

- Aardwolf

- African Wild Cat

- Cape Porcupine

- Steenbok

- Scrub Hare

- Black-Backed Jackal

- Skunk

- Cape Fox

- Blesbok

- Warthog

- Eland

- Sable

- Roan

Bird Ringing in the Karoo

Bird ringing (i.e., bird banding) assists scientists in studying the lifespan, migration patterns, and habits of individual birds. During the course, Dieter and the trainees set up the ringing nets at various locations across the New Holme Farm. The nets gently captured birds and trainees carefully extracted them. Once captured, the birds were identified, weighed, measured, checked for brood patches (evidence of nesting), and adorned with a small aluminum ring that had a unique identification number.

When ringed birds are recaptured, found deceased, or otherwise discovered, information about the sighting should be uploaded to SAFRING. This contributes to an online database for ringed birds in Southern Africa which can be used for research and policy purposes.

Row 2: Little Stint, Cape White-Eye, African Hoopoe

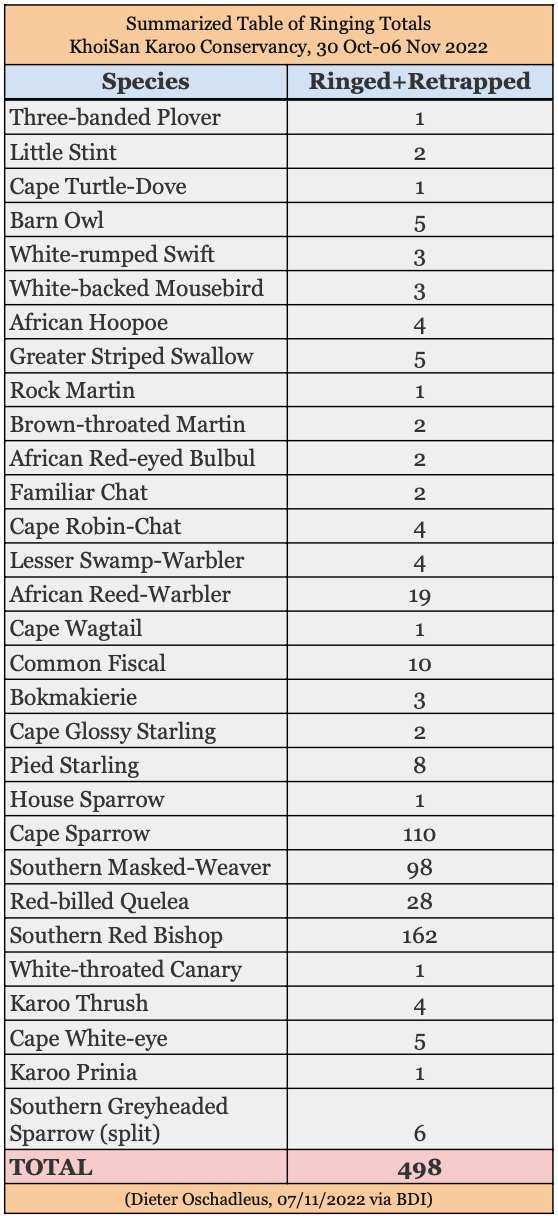

To view the complete dataset and read Dieter’s summary of the bird ringing course please check out his post here.

Birding, Citizen Science, and Connections to Nature

During our final dinner as a team, I conducted some brief, informal interviews so I could better understand the significance of birding and citizen science for participants. I’ve transcribed excerpts from these conversations below.

***

Interviewer: How does it feel to contribute to something bigger than a personal passion? To feel like your interest in birds is going somewhere else?

A: It feels amazing. I’ve asked questions about where the data we’ve collected this week will be applied to. Because the data you collect is so small, you don’t realize that it can actually make a contribution… that it can make a big difference and have a bigger outcome. This is the first time I’ve been in the company of actual scientists, and it’s a very new territory for me. It feels exciting and refreshing to contribute to something like this…

A: I think it’s very important for people like myself to come on these courses because I’m not going to change my profession, but I am going to influence and teach people like myself by speaking in layman’s terms. Being in the field and being able to ask questions is invaluable because it helps me build knowledge and understanding.

Interviewer: It brings science down to the conversation level and the life level.

A: Yes, because it happens in your garden. The way I actually got into birding—which I think is a common story—is that I liked birds but I couldn’t identify most of the species at my bird feeder. I really wanted to know the specific details.

Interviewer: Has knowing the specific details influenced your relationship to birds?

A: Of course, definitely, it has made me more curious, more adventurous to go out and listen, to tune myself more into the environment and new areas, even if I don’t know what to expect there.

***

Interviewer: What is your perspective on birding and citizen science? What motivates your involvement?

S: For me it’s just a passion for birds, I’m just an enthusiast. I’m not a scientist.

Interviewer: Do you find that your experiences with birds impacts other areas of your life? Does birding become more than just a passion?

S: Yes, of course. It impacts on everything. It’s everything. It’s the spiders, it’s the scorpions, it’s the lifestyle, it’s the recycling, it impacts everything.

***

Note: Some of the responses were edited for clarity, brevity, and grammar. To protect privacy, full names were omitted.

Throughout the course of our trip to the Karoo, the team and I had many conversations about citizen science, ecological knowledge, and birding. It was really interesting to see how a passion for a birds can ignite involvement in citizen science-based courses and fieldwork, which in turn allows people to further cultivate their personal relationships with nature. As these interviews demonstrate, citizen science may have a ripple effect on behaviours, relationships, and perspectives.

I am grateful for Les Underhill and Dieter Oschadleus for inviting me along on the course and for being such kind, generous, and helpful people. Ryan and Jana, thank you for hosting us for lunch at Rietaar and for showing us around the farm! To the staff of New Holme Nature Lodge, many thanks for your wonderful hospitality. Finally, to A, K, S, J, and D: thank you for sharing your passion for birds with me, entertaining my questions, and making me feel so welcome. I am inspired by you!