Cover image of Cape Vulture by Pamela Kleiman – Underberg district, KwaZulu-Natal – BirdPix No. 274705

Vultures belong to the Family: ACCIPITRIDAE. This family also includes eagles, hawks, buzzards, kites etc. Members are all carnivorous, and most are medium to very large birds with strongly hooked bills.

Identification

The Cape Vulture is a very large species, weighing up to 10.8 kg and can attain a wingspan up to 2.6 m. The sexes are alike but females are slightly larger.

Giant’s Castle, KwaZulu-Natal

Photo by Johan van Rensburg

Adult Cape Vultures have bluish-grey heads, covered in short, white, hair-like feathers. The face is bare and can turn reddish when they are excited. The neck is long and bluish-grey, with a collar of fluffy white feathers around the base. A crop patch is present below the neck with short, dark brown feathers. It is flanked by two bare, light blue ‘breast-patches’, but these are not always visible. The overall body colouration varies from creamy off-white to buff-coloured and the back feathers are mottled with broad streaks. Perched birds show a diagnostic row of dark spots on the wing, just above the black flight feathers. The short tail is blackish brown. The bill and cere are black and the eyes are dull yellow. The legs and feet are black.

Adults in flight appear pale from below. The primaries are blackish and the secondaries are pale with a distinct, dark terminal bar.

Mabula Game Reserve, Limpopo

Photo by Lance Robinson

Juvenile and immature birds go through a gradual transition into adult plumage that takes several years. Both are darker overall than the adults with dark buff streaks, which are especially noticeable on the underparts. The head is covered with woolly white down and the bare skin on the hind neck has a pinkish tint. The ‘breast-patches’ are reddish. They also have lance-shaped ruff feathers that eventually turn fluffy as they reach adulthood. Young birds slowly become paler as they mature and the streaked undersides are the last juvenile feature to be lost. The eyes are brown, only turning yellow in their fifth or sixth year. The skin on their necks is dark with pink tinges.

Vulpro, Gauteng

Photo by Anthony Paton

Juveniles, when seen in flight from below, show blackish primaries and dark secondaries with grey-brown tips. If seen from above, the greater covert tips form a diagnostic narrow white stripe across the wing. Soaring immatures resemble the adults but generally have darker secondaries and show a row of black spots along the coverts near the base of the flight feathers.

Ingula Nature Reserve, KwaZulu-Natal

Photo by Lance Robinson

Naude’s Nek, Eastern Cape

Photo by Jorrie Jordaan

Status and Distribution

The Cape Vulture is essentially endemic to southern Africa, with occasional vagrants reaching southern Zambia. It is a locally common resident in the core of its range but is scarce to rare elsewhere. The Cape Vulture is listed globally as endangered.

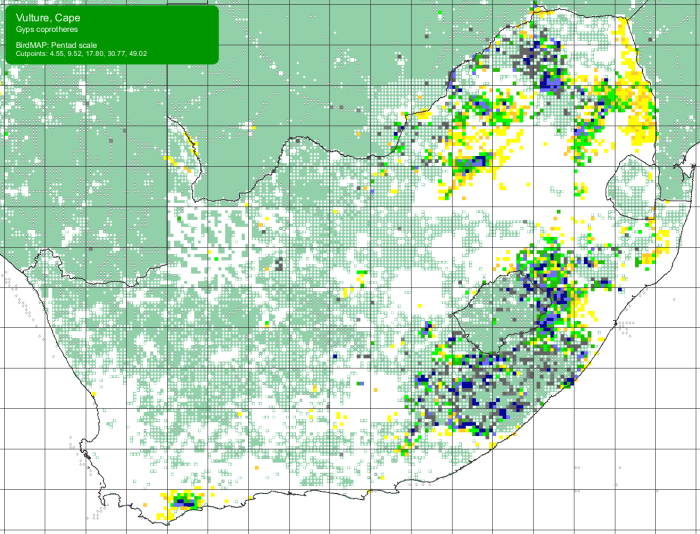

It is fairly widely distributed in southern Africa. The Cape Vulture is most widespread in South Africa, particularly in the east and north with a small, isolated population in the south-Western Cape. It also occurs in central and northern Namibia, south-eastern Botswana, western and southern Zimbabwe, south-western Mozambique, and eSwatini (Swaziland). Sadly, both the range and population of the Cape Vulture have decreased significantly over the last 100 years, and the Cape Vulture is now extinct as a breeding species in Namibia, Zimbabwe, eSwatini (Swaziland) and probably also Mozambique.

Giant’s Castle, KwaZulu-Natal

Photo by Johan van Rensburg

The remaining breeding colonies are located in two, now mostly disjunct, regions. The first includes colonies in eastern Botswana and the Limpopo, North West and Gauteng provinces. The second is centred around the Drakensberg Mountain range in the Lesotho highlands, western KwaZulu-Natal and the Eastern Cape. Additionally, a remnant and isolated colony persists in the south-Western Cape.

The current distribution of the Cape Vulture shows that it has become greatly reduced or extinct in many areas away from its core range. This is most obvious in commercial, small-stock farming regions in the Karoo, Fynbos and Grassland biomes. The now fragmented range of the Cape Vulture is evident in the latest distribution map (see above).

Near Hekpoort, Gauteng

Photo by Andrew Keys

The Cape Vulture faces many threats to its continued survival. The greatest threat is from poisoning, which comes in two forms, either direct or indirect poisoning.

- Indirect poisoning is largely due to irresponsible farmers who prepare and place poisoned baits to control live-stock predators such as jackals.

- Direct poisoning occurs when vultures are deliberately poisoned by poachers to prevent the birds from alerting authorities when they circle over recent kills. They are also directly poisoned to harvest and sell their body parts for belief-based use.

Other major threats to the Cape Vulture include:

- Collisions with energy infrastructures such as wind farms

- Electrocutions on electricity lines and pylons

- Reduced availability of food sources

- Loss of breeding and foraging habitat

- Human disturbance at breeding colonies

Near Elliot, Eastern Cape

Photo by Walter Neser

Habitat

Sani Pass, KwaZulu-Natal

Photo by Ryan Tippett

The Cape Vulture is reliant on tall cliffs for breeding, but they wander widely into other habitats when searching for food. Cape Vultures forage over a range of open habitats like grassland, scrub and savanna. The Cape Vulture is scarce in dense woodlands. Its current distribution is closely associated with subsistence communal-grazing areas, characterised by high stock losses and low use of poisons. They also scavenge in large conservation areas such as the greater Kruger National Park and game reserves in north-eastern Kwazulu-Natal, but do not breed in these reserves.

Underberg district, KwaZulu-Natal

Photo by Pamela Kleiman

The Cape Vulture occurs and breeds from near sea level in the Western Cape up to 3100 m above sea level in the Lesotho highlands.

Near Hekpoort, Gauteng

Photo by Andrew Keys

Behaviour

The Cape Vulture is usually seen in groups of up to 100, but foraging birds may be seen in twos and threes. Small groups of Cape Vultures roost at night on trees and electricity pylons while larger groups roost on cliffs. They frequently gather at water to bathe and drink. They lie or stand with their wings outstretched after bathing to dry off, followed by preening.

Near Hekpoort, Gauteng

Photo by Andrew Keys

Cape Vultures are generally resident but can be somewhat nomadic when not breeding. Birds have been recorded wandering up to 1200km during the non-breeding season, especially immatures prior to their first nesting attempt.

Queenstown district, Eastern Cape

Photo by Craig Peter

They range widely when searching for food. Cape Vultures forage in flight and carrion is identified by sight alone. They mostly search for medium-sized to very large mammal carcasses. Foraging birds soar high above open habitats. They spread out, scanning for signs of food by watching each other, and also the activities of other avian and mammalian scavengers.

Near Hekpoort, Gauteng

Photo by Andrew Keys

Once a carcass has been spotted, Cape Vultures will dive and descend rapidly. They arrive promptly at a carcass, and often in large numbers. At first, they will perch in nearby trees or stand around assessing the surroundings. Once it is deemed safe they will move in to feed. The Cape Vulture dominates most other vultures at a carcass, except adult Lappet-faced Vultures (Torgos tracheliotos), and they will occasionally attempt to steal food from other vulture species. They often have to wait for Lappet-faced Vultures or mammalian scavengers to open large, thick-skinned carcasses.

Thornybush Private Game Reserve, Limpopo

Photo by Vaughn Jessnitz

Cape Vultures feed mostly by reaching deep inside a carcass, slicing off flesh with the sharp edges of the upper mandible. They eat rapidly, aided by grooves and serrations on the tongue. The crop can be filled within 5 minutes, which is enough food to sustain them for 3 days! They consume muscle tissue, organs, intestines and bone fragments and mostly avoid tougher material like thick skin and ligaments.

Golden Gate Highlands National Park, Free State

Photo by Erena Neubert

The Cape Vulture is monogamous and probably pairs for life. They nest colonially on tall cliffs. Colonies can number up to 1 000 pairs, but these days few colonies support more than 100 pairs. They are not territorial.

Oribi Vulture Hide, KwaZulu-Natal

Photo by Lia Steen

The nest is placed on a cliff ledge and is a fairly sparse, platform of sticks with a shallow bowl, lined with leaves and grass. The outside diameter of the nest can reach 1m across. It is built entirely by the female although the male gathers most of the nesting material. Pairs often re-use the same nest site in subsequent breeding seasons.

Magaliesburg, North West

Photo by Rihann Geyser

Cape Vultures breed from March to July. A single off-white egg is laid per clutch. Incubation is shared almost equally by both sexes. The incubating bird’s shift lasts for 1 or 2 days at a time, while its mate is away foraging. The incubation period last for up to 58 days.

Once the egg hatches the young nestling is brooded continuously for up to 72 days. The nestling is fed on regurgitated food by both parents. Calcium rich bone fragments are very important in the nestlings diet. The nestling period lasts for up to 170 days before fledging. Fully fledged juveniles remain dependant on their parents for up to 221 days. The parents will then chase away the the immature bird before the start of the next egg-laying season. Young Cape Vultures take 4 to 6 years to reach sexual maturity.

Giant’s Castle, KwaZulu-Natal

Photo by Richard Johnstone

Further Resources

Species text from the first Southern African Bird Atlas Project (SABAP1), 1997.

The use of photographs by Andrew Keys, Anthony Paton, Craig Peter, Erena Neubert, Johan van Rensburg, Jorrie Jordaan, Lance Robinson, Lia Steen, Pamela Kleiman, Richard Johnstone, Vaughan Jessnitz and Walter Neser is acknowledged.

Virtual Museum (BirdPix > Search VM > By Scientific or Common Name).

Other common names: Cape Griffon (Alt. English); Kransaasvoël (Afrikaans); iNqe (Zulu); lxhalanga (Xhosa); Diswaane, Lenông (Tswana); Kaapse Gier (Dutch); Vautour chassefiente (French); Kapgeier (German); Grifo do Cabo (Portuguese)

A list of bird species in this format is available here.

Recommended citation format: Tippett RM 2024. Cape Vulture Gyps coprotheres. Biodiversity and Development Institute. Available online at https://thebdi.org/2024/07/22/cape-vulture-gyps-coprotheres/

Vulpro, Gauteng

Photo by Andrew Keys