Cover image: Greater Honeyguide by Phil White – Mbuluzi Game Reserve, eSwatini – BirdPix No.103314

Honeyguides belong to the Family: INDICATORIDAE and it is the only family of birds in which every member is exclusively brood parasitic. They are intriguing and unusual birds with an array of fascinating adaptations.

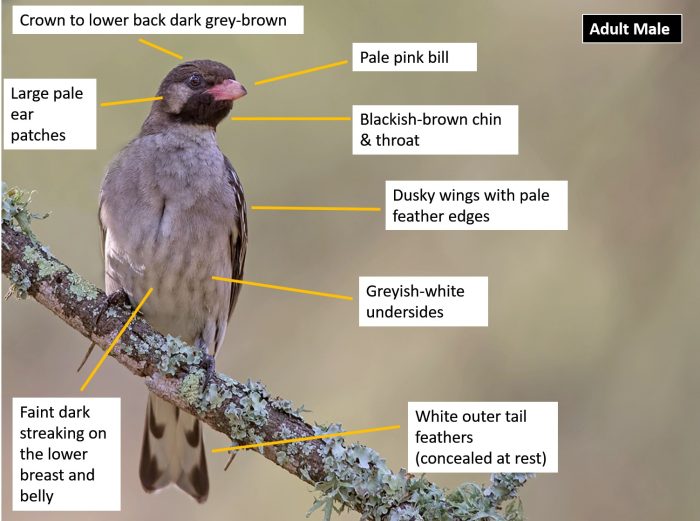

Identification

The Greater Honeyguide is a large, greyish-brown honeyguide. It is unique among honeyguides in that they are sexually dimorphic, differing in plumage colouration.

Baviaanskloof, Eastern Cape

Photo by Gregg Darling

Adult males are more colourful than females and have a pink bill, black throat and white ear coverts, and often show a small yellow shoulder patch. The upperparts, from the forehead to the lower back are dark olive-brown to greyish brown. The wings are dusky brown with pale edges to the coverts. The tail is blackish with broad, white outer tail feathers (present in both sexes and juveniles). The white outer tail feathers are usually only visible in flight or when the tail is spread. The chin and throat are black, while the rest of the underparts are greyish-white, sometimes with faint, dark streaking on the middle breast to the belly. The eyes are dark brown and the legs and feet are grey.

Underberg district, KwaZulu-Natal

Photo by Pamela Kleiman

Females resemble males but are duller and slightly paler above. They also lack the male’s distinctive head markings. Females also have a dark blackish (not pink) bill.

Juveniles are plain brown above with a darker brown crown, neatly separated from the yellowish throat. They often also have a greyish eye-ring. Their underparts are distinctly yellowish below, especially on the breast, making them fairly easy to identify.

River of Joy, Free State

Photo by Jorrie Jordaan

Male Greater Honeyguides with their pink bills, and distinctive facial markings are not easily mistaken for other species. Females are more difficult to identify and can resemble bulbuls, but differ in behaviour, perching conspicuously and with a more upright posture. Females most resemble the Scaly-throated Honeyguide (Indicator variegatus) but can be distinguished by the plain, unstreaked breast and greyish-brown (not olive brown) back and wings.

Status and Distribution

The Greater Honeyguide is widespread across sub-Saharan Africa and is absent only from tropical forest and desert regions. In southern Africa it occurs mainly in the north and east, extending along the southern coast into the Western Cape. It is absent from most of Namibia, Botswana and the drier regions of the central and northern Karoo.

The distribution of the Greater Honeyguide parallels that of its primary brood hosts, and not that of its main food source the African Honeybee (Apis mellifera)

The Greater Honeyguide is generally uncommon throughout its range. It is most numerous in the north and east of southern Africa and less so in the south. Population densities of the Greater Honeyguide are everywhere low.

There is no evidence that the distribution of the Greater Honeyguide has declined since the beginning of the 20th century. Its range has in fact expanded in South Africa, especially in the Western Cape and the fringes of the Karoo. This is mainly due to the widespread planting of trees and the development of parks and gardens. It may have also benefited from bee farming in several areas. The elimination of wild beehives might cause local population decreases.

Lake Langano, Ethiopia

Photo by Maans Booysen

Habitat

The Greater Honeyguide is found mostly in the Savanna biome, occupying a wide range of woodland types. It also inhabits riverine forest and forest edge but avoids areas of dense forest. The Greater Honeyguide has adapted readily to plantations of pine and eucalypts, and is also found along treed watercourses in some arid areas, notably on the Orange River. The Greater Honeyguide also occurs in fynbos, grassland and the moister parts of the Karoo, but in these habitats it is restricted to areas with at least some trees.

Ndumo Game Reserve, KwaZulu-Natal

Photo by Ryan Tippett

Behaviour

The Greater Honeyguide is normally solitary, secretive and seldom seen, unless calling at a song post or when guiding. They often sit perched for long periods.

Woodland Hills Wildlife Estate, Free State

Photo by Rick Nuttall

Song posts may be used year-round, but mostly in the breeding season season. These call sites are used by one or more males for generations. Males show little if any aggression to one another at a song post even when females are present. Their characteristic and far-carrying ‘vic-torrr’ call is distinctive, as is the excited, rattling chatter of the guiding call. Males can also produce a drumming sound like that of a snipe, although not as intense, by vibrating the fanned tail in swooping display flights. The normal flight is fast and undulating.

Edenvale, Gauteng

Photo by Bryan Groom

Greater Honeyguides are inquisitive and readily attracted to disturbances like the alarm-calls of other birds and the mobbing of predators. They regularly attend mixed-species foraging flocks and are also known to be attracted to fire. They drink water frequently and waiting patiently at water is one of the best ways to see them.

Tsanakona, Botswana

Photo by Gert Myburgh

Greater Honeyguides eat beeswax, adult bees, their eggs and larvae. They do not eat honey and seem to avoid it altogether, perhaps due to its stickiness and potential to impair the function of their feathers. Beeswax is important in the diet and honeyguides have symbiotic micro-organisms in the gut that help to digest the wax. The ability to eat wax is known as cerophagy and is rare in vertebrates. Greater Honeyguides will also feed on other insects such as termite alates, caterpillars, ants, beetles and grasshoppers.

Edenvale, Gauteng

Photo by Bryan Groom

They have an acute sense of smell and locate beehives primarily by scent, but also by sight, quietly observing the coming and going of bees.

It is unknown exactly how important beeswax is in their diet. Honeycomb is a relatively scarce and hard to obtain food source that the birds themselves are not well equipped to access. Honeyguides are not immune to bee stings but they do have a tougher than usual skin and dense feathering that can provide them with some protection.

Vleidam guest farm, Western Cape

Photo by Zenobia van Dyk

In most instances honeyguides would require help to access honeycomb. It has long been suspected that Greater Honeyguides lead Honey Badgers (Mellivora capensis) to beehives, however this has never been adequately proven. Honey Badgers have a highly developed sense of smell and have no problem finding beehives by themselves. They are also very well equipped to access the hives and to tear them apart. Honey Badgers seen feeding at beehives usually have one or more honeyguides in attendance. The most likely scenario here is that the honeyguides were attracted by the commotion and the smell of the exposed honeycombs.

Thabazimbi district, Limpopo

Photo by Neels Putter

Greater Honeyguides are most well known for their ability to lead humans to beehives. This guiding habit is well developed and is innate and not learned. Adults of both sexes, and less frequently immatures, guide at any time of the day and throughout the year.

The honeyguides know the locality of beehives within their home ranges and these birds display and chatter excitedly to draw human attention to themselves. Once noticed, the bird will approach the human. It then flies in exaggerated dipping flight to another exposed perch, where it awaits the person before the display and chattering is repeated. This process carries on until the hive is reached. If the bird is not followed, it will double back and repeatedly try to draw the persons attention. Once the hive is reached, the bird alters its behaviour, sitting motionless and in silence while the hive is plundered.

Kruger National Park, Limpopo

Photo by Anthony Paton

In traditional folklore it has been said that if the honey-gatherers do not leave some honeycomb behind for the bird, that next time the honeyguide will lead them to a Black Mamba or some other peril!

This guiding behaviour is confined to certain areas of the birds distribution, being entirely absent from others. Honeyguides are believed to have associated with human honey-gatherers for many thousands of years. Unfortunately this symbiotic relationship has disappeared from many areas of Africa due to a lack of response by humans to the guiding call. This is likely the result of modern people no longer needing, or wanting to forage for food in the wild and may eventually lead to the complete loss of this complex bird-human relationship.

Baviaanskloof, Eastern Cape

Photo by Desire Darling

Greater Honeyguides are brood parasitic, targeting a wide range of hole-nesting birds. In southern Africa at least 39 host species have been recorded with a number of other species suspected as hosts. The most frequent hosts include bee-eaters, martins, kingfishers, starlings, tits, barbets, woodpeckers and woodhoopoes.

Prior to breeding, males begin to call more frequently from their song posts. Males call on and off throughout the day from September to March. Females are attracted to males at the song posts and their arrival coincides with ovulation. Greater Honeyguides are polygynous, whereby a male mates with multiple females through the breeding season. Males then play no further role in the breeding process.

Klerksdorp district, North West

Photo by Tony Archer

Mated females then head off to seek out the nests of host species. Once a potential host nest is found the female sits quietly and observes the activities of the host birds. She then carefully picks the right moment to sneak into the nest. A single glossy white egg is (usually) laid per nest, which she does quickly. It is strongly suspected that she will remove a host egg for every egg she lays. The remaining host eggs are then often punctured or damaged, increasing the survival chances of the honeyguide chick.

Inhamitanga, Mozambique

Photo by Maans Booysen

Greater Honeyguide eggs require a shorter incubation time than those of their hosts and allows for the honeyguide chick to hatch earlier, giving them an additional survival advantage. However, the exact incubation time has not yet been recorded.

Newly hatched honeyguide chicks have lethal bill hooks on both mandibles that they use to kill the host chicks. These hooks are lost within several days of hatching, having already served their purpose. Chicks remain in the host nest for a long time (up to 38 days) and are almost independent on leaving. Greater Honeyguide fledglings are often still fed by the host for another 7 days or so. Sometimes the confused foster parent will simultaneously feed the perched honeyguide fledgling, and then mob it once it flies.

Zimanga Game Reserve, KwaZulu-Natal

Photo by Ryan Tippett

Further Resources

Species text for the Greater Honeyguide in the First Southern African Bird Atlas Project (SABAP1), 1997.

The use of photographs by Anthony Paton, Bryan Groom, Desire Darling, Gert Myburgh, Gregg Darling, Jorrie Jordaan, Maans Booysen, Neels Putter, Pamela Kleiman, Phil White, Rick Nuttall, Tony Archer and Zenobia van Dyk is acknowledged.

Virtual Museum (BirdPix > Search VM > By Scientific or Common Name).

Other common names: Grootheuningwyser (Afrikaans); iNgede ,iNhlavebizelayo (Zulu); Intakobusi (Xhosa); Tshetlho (Tswana); Grote Honingspeurder (Dutch); Grand Indicateur (French); Großer Honiganzeiger, Schwarzkehl-Honiganzeiger (German); Indicador-grande (Portuguese).

List of species available in this format.

Recommended citation format: Tippett RM 2024. Greater Honeyguide Indicator indicator. Biodiversity and Development Institute. Available online at https://thebdi.org/2024/05/22/greater-honeyguide-indicator-indicator/

Baviaanskloof, Eastern Cape

Photo by Desire Darling