View the above photo record (by Luke Kemp) in FrogMAP here.

Find the Cape Caco in the FBIS database (Freshwater Biodiversity Information System) here.

Family Pyxicephalidae

CAPE CACO – Cacosternum capense

Hewitt, 1925

Identification

C. capense is the largest member of the genus, attaining a maximum snout-vent length of 39 mm. It has an elongated body with a relatively small head and a horizontal pupil. The fingers and toes lack webbing. The palmar tubercles are poorly developed, the outer metatarsal tubercles are absent, and inner metatarsal tubercles are prominent and flange-like. A pair of large blister-like glands is present on the lower back, at the level of the urostyle, with another pair on the flanks, while numerous smaller glands are often scattered over the rest of the dorsum.

The dorsum varies in colour from grey to cream or light brown, with speckles and flecks of dark brown, orange or green. The ventral surface is creamy white, distinctively marked with large, irregular, olive to black blotches, and males have a dark throat.

The advertisement call is a harsh “creak”, about 0.2 s in duration, uttered repeatedly at a rate of about two per second (Passmore and Carruthers 1995).

Habitat

C. capense inhabits flat or gently undulating low-lying areas with poorly drained loamy to clay soils, where it breeds in shallow, temporary, rain-filled pools and pans that form during the winter months. It also occurs in more sandy habitats but appears to be absent from the deep sands of the Cape Flats and adjoining coastal regions. The natural vegetation, which has been largely destroyed by urban development and agricultural activities, comprises the following vegetation types: West Coast Renosterveld, Central Mountain Renosterveld and, to a lesser extent, Sand Plain Fynbos, Dune Thicket and Mountain Fynbos.

Prior to urban and agricultural development, the area inhabited by C. capense was mostly covered in renosterveld vegetation which is now one of the most threatened and poorly conserved vegetation types in southern Africa. However, this would not appear to be of critical importance for this species, as about 90% of its recorded breeding sites occur in modified habitat, particularly agricultural lands. These are mainly wheat fields, but also include lands cultivated for other crops (e.g. lupins and oats), vineyards, orchards, fallow lands and pastures. Owing to the large-scale destruction of natural vegetation, there are relatively few breeding sites in undisturbed habitat.

Behaviour

C. capense is a winter breeder, with the commencement and duration of the breeding season being determined by the rainfall pattern. Breeding usually starts after the second heavy rains of winter, and continues in response to heavy bouts of rain. C. capense has been found to breed mostly in June–August, but calling activity has been heard as early as 24 April near Hermon (pers. obs.) and breeding has been recorded on 3 September in the Piketberg area (M. Burger and J.A. Harrison; pers. obs.). Males call occasionally during the day but mostly at night. At a prime breeding site under ideal conditions, more than 70 calling males were heard, but breeding aggregations are usually considerably smaller. Calling males are usually scattered and seldom form dense choruses. Males remain partially submerged in the water while calling and duck below the surface at the slightest disturbance.

Spawning was briefly described by Rose (1926). The eggs are laid in jelly clusters with each egg enclosed in a capsule. Egg clusters are attached to submerged vegetation such as grass stalks, and the number of eggs per cluster can vary considerably. In nine clusters (from one breeding group), the eggs numbered 57–400 (Rose 1926), and in 13 clusters found at a Klipheuwel breeding site, the eggs numbered 19–54. The development of the eggs and tadpoles was described by De Villiers (1929). The tadpoles are benthic and the duration of metamorphosis is probably correlated with factors such as temperature and the availability of food and water. In captivity, the tadpoles of eggs laid on 10 June completed metamorphosis from 7 September onwards (Rose 1926). Tailed froglets were found near Paarl on 10 September (pers. obs.).

This species aestivates underground during the dry season. Its survival in regularly cultivated lands suggests that the frogs may burrow to depths below the reach of conventional ploughs.

Nothing is known of the diet of this species and no predators have been recorded. C. capense adults appear to secrete a poisonous substance from their skin glands, as it was observed that frogs of other species died when placed in the same vivarium (Rose 1926).

Status and Conservation

Status

C. capense occurs in at least four populations. More than 90% of the area it occupies consists of modified habitat. Furthermore, it is estimated that more than 50% of its natural habitat has been lost over the last 70 years (Harrison et al. 2001), mainly in the southern part of its range.

C. capense occurs in three protected areas, which together represent less than 5% of its historical distribution area: J.N. Briers-Louw Provincial Nature Reserve (near Paarl), Elandsberg Private Nature Reserve (near Hermon) and the adjoining Voëlvlei Provincial Nature Reserve.

This species was previously listed as Rare (McLachlan 1978), and Restricted (Branch 1988), and is currently listed as Vulnerable (Harrison et al. 2001; this publication). This is based on an extent of occurrence <20 000 km2, area of occupancy <2000 km2, severely fragmented habitat, continuing decline in the extent of occurrence, area of occupancy, extent and quality of habitat and the number of locations/subpopulations and mature individuals. The species is legally protected by the Nature Conservation Ordinance 19 of 1974, but is not listed by CITES.

Threats

C. capense is threatened primarily by urban expansion and, to a lesser degree, by changes in the use of agricultural land and invasive vegetation. These have resulted in the loss, degradation and fragmentation of its habitat.

Urban development has resulted in the draining and/or filling of breeding sites. Although most remaining sites are in agricultural lands, intensive agriculture is a threat, and the practice of draining surplus water from cultivated lands prevents or restricts the formation of breeding pools during the wet winter months.

The widespread use of fertilizers, herbicides and pesticides in agricultural lands presents an additional threat, but the exact extent and level of this threat is unknown. The spread of invasive vegetation threatens C. capense habitat in places, particularly where invasive grasses and/or herbs form a thick, impenetrable ground cover.

Climate change due to global warming and reduced rainfall (Midgley et al. 2001) present a potential threat that would lead to a further loss of breeding habitat and the contraction of the distribution range of this species.

Recommended conservation actions

The distribution and conservation status of C. capense is monitored by the Western Cape Nature Conservation Board (De Villiers 1997a) as part of a threatened species monitoring programme. However the effect of fertilizers, herbicides and pesticides on the species requires further investigation, because most breeding sites are situated on agricultural land. The sites used by frogs for aestivation in summer should be identified as this may involve habitat other than the breeding habitat.

The future of C. capense depends increasingly on its ability to survive in the agricultural lands that have replaced most of its natural habitat. In this regard, it is important to enlighten farmers about this species and to encourage them to conserve its habitat on their lands and, as far as possible, to leave breeding ponds undisturbed during the winter breeding season.

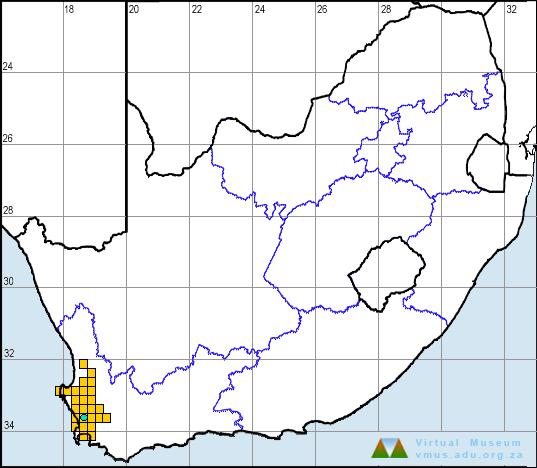

Distribution

C. capense is endemic to the winter-rainfall region of the Western Cape where it is restricted to altitudes below 280 m in areas that receive an annual rainfall of 300–1000 mm. Most of its distribution range is situated in the lowlands west of the Cape fold mountains, extending from the Cape Flats northward for 200 km to the Graafwater district, including a small population in the Olifants River valley. Another population is present in the Breede River valley about 80 km northeast of the Cape Flats, between Worcester and Tulbagh.

The description of the species followed its discovery in 1924 at “Rondebosch Golf Links” on the present Rondebosch Common (3318CD; Rose 1926, 1929). During the 50-year period following its discovery, this elusive frog was recorded from only a few additional localities: Stellenbosch (3318DD); Malmesbury (3318BC); Kuils River, Durbanville, Kraaifontein (3318DC); and Faure (3418BA). In 1976, a survey by J.C. Greig and R.C. Boycott of the then Cape Department of Nature and Environmental Conservation, produced a number of new locality records, extending the known range from Somerset West to the Darling, Moorreesburg and Gouda districts, and bringing to light a new population in the Breede River valley. During this survey, the species was recorded from 11 new grid cells, increasing the number to 16 (De Villiers 1988d). During the 1990s, on-going monitoring (De Villiers 1997a) significantly extended the range of the species northwards, to include the areas from Eendekuil to Piketberg to Velddrif (3218CD, DB, DC, DD) and an additional record from the Swartland (3319CA). The frog atlas surveys have added five additional grid cells to the known range. These records include the western limit of its distribution range in the Vredenburg area (3217DD), the present northern limit of its distribution range near Graafwater (3218BA), and a small population in the Olifants River valley (3218BD).

In all, C. capense has been recorded in 26 quarter-degree grid cells. Since 1990, despite an ongoing monitoring programme (De Villiers 1997a), there has been no sign of C. capense in three of the previously recorded grid cells. These include the Worcester (3319CB), Somerset West (3418BB) and Cape Peninsula (3318CD) areas. In fact, the only known C. capense locality on the Cape Peninsula is the site, on the present Rondebosch Common, where this frog was first discovered, and which unfortunately became a rubbish dump (Rose 1950) and was filled in and covered by invasive kikuyu grass (McLachlan 1978).

Further Resources

Virtual Museum (FrogMAP > Search VM > By Scientific or Common Name)

More common names: Cross-marked Frog, Cape Dainty Frog (Alternative English Names); Kaapse Caco, Kaapse Blikslanertjie (Afrikaans)

Recommended citation format for this species text:

de Villiers AL, Tippett RM. Cape Caco Cacosternum capense. BDI, Cape Town.

Available online at http://thebdi.org/2022/02/16/cape-caco-cacosternum-capense/

Recommended citation format:

This species text has been updated and expanded from the text in the

2004 frog atlas. The reference to the text and the book are as follows:

de Villiers AL 2004 Cacosternum capense Cape Caco. In Minter LR

et al 2004.

Minter LR, Burger M, Harrison JA, Braack HH, Bishop PJ, Kloepfer D (eds)

2004. Atlas and Red Data Book of the Frogs of South Africa, Lesotho and

Swaziland. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, and Avian Demography

Unit, Cape Town.