Good afternoon, naturalists! Time for an update on Operation Feed the Birds, and a few new insights into garden ecology.

Let’s begin with the birds.

Since my first blog post, the two bird feeders have been kept busy, entertaining visitors around the clock. One of my neighbours has a very active feeder, and I suspected that the birds from his garden would locate this hot new local food source quickly. And yet, their speed still surprised me! Within exactly 1 hour and 5 minutes (yes, I did spend an entire day by the window with my binoculars), a male and female Cape Sparrow were furtively darting to and from the tree feeder. The first few birds were extremely wary; if a hinge creaked, or a dog barked, or if I so much as breathed, they were off like a flash.

As the day wore on, though, the birds began to grow accustomed to the noises and sights of the garden, and by the end of the first week they barely flinched if I opened the door. My species list for the cottage slowly continued to climb—I began seeing birds at my feeder not previously observed in the garden. Southern Masked Weaver, Pin-tailed Whydah, and (miraculously) a single Southern Grey-headed Sparrow began to make regular appearances. (I have dubbed the sparrow “Jack.” He hangs around now, always on his own).

Needless to say, since those first few days, the feeders have become a veritable hive of activity. Laughing Doves and Red-eyed Doves, chests puffed out, strut importantly below the feeders, collecting seeds and filling the air with their burbling coos. A hot-headed Ring-necked Dove chases off Laughing Doves that come too close, and even the Cape Robin-Chat now makes regular appearances, perhaps sensing safety in the presence of so many birds.

Broadly, the sheltered feeder receives more visitors in a 10-minute period and experiences a faster overall decline in seed level than the open feeder.”

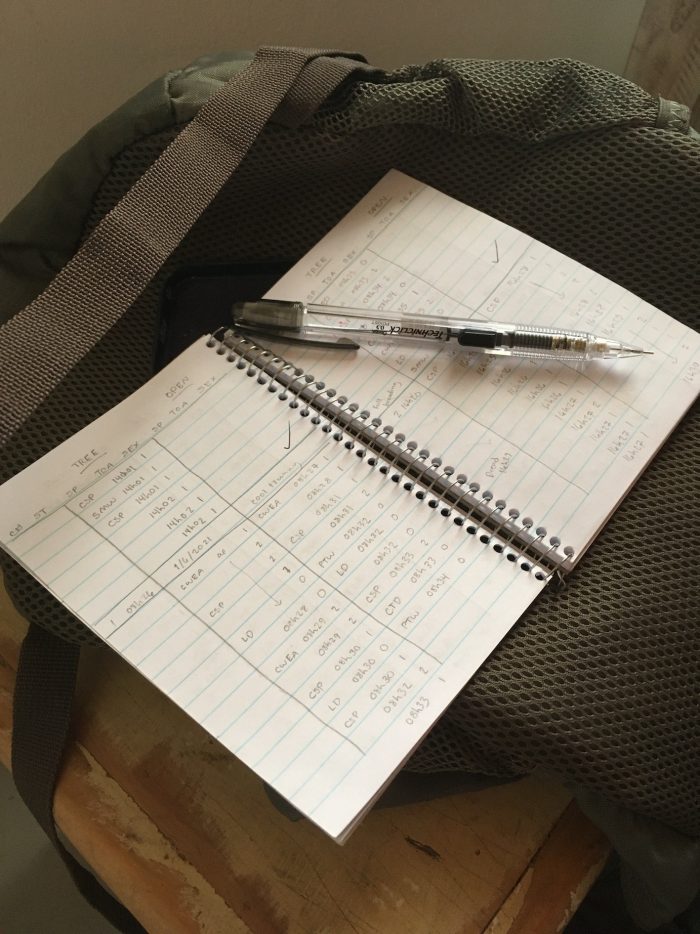

Clearly, in terms of use, the feeders are a success. At least twice a day (and more often if I can), I sit by the window with a timer, a notebook, and a pencil, and record the birds arriving at each feeder in a 10-minute block. At the end of the day, I measure the level of seed in each feeder. Already, patterns are emerging! Broadly, the sheltered feeder receives more visitors in a 10-minute period and experiences a faster overall decline in seed level than the open feeder.

Though the pattern of use for the tree-sheltered feeder versus the open feeder is intriguing (and we will explore it further in a future blog), my thoughts over the past few weeks have been equally preoccupied with the garden itself. And that brings us to our next set of ecological concepts in this blog series: colonisation and succession.

What do these words (which sound like they belong in political history) have to do with birds in a garden?

To answer that question, we first need to understand how a garden ecosystem forms.

Let’s start with an example.

Imagine that you are on a volcanic island. A volcano erupts, lava flows over the land and into the ocean, and as it cools, new, bare rock is formed. It has never had any plant life on it; it has never been inhabited by any species—it is new, untouched, and barren. As rain falls, and the wind blows, and the sun continues to shine, life slowly begins to arrive.

Pioneer species…are organisms with seeds or spores that can travel long distances by wind or water.”

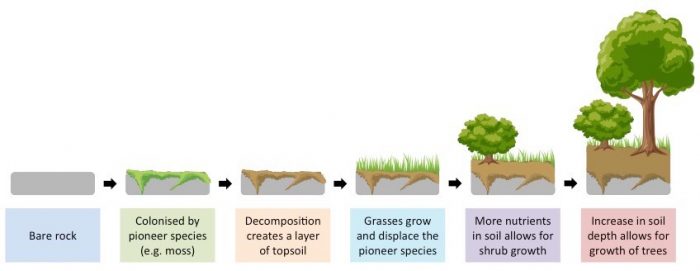

These are pioneer species; organisms with seeds or spores than can travel long distances by wind or water. Things like algae, fungi, and lichen, which spread across the bare rock, slowly breaking it down. And as these species spread, some die off, and wind and water deposit more and more living material. Microorganisms continue to break down these layers of “stuff,” over time forming the rich, organic matter that makes up soil.

Once soil is present, new species are able to move in. Grass, which takes in its nutrients from soil, spreads over the land, and displaces the pioneer species. As the grass grows, it continues adding material and nutrients back into the soil, making it deeper and richer, and paving the way for bigger plants, like shrubs.

Primary succession…describes the succession of species and events that build on one another to create an established, living community”

This pattern of moving in, enriching the soil, and making space for something new continues, eventually allowing massive organisms like trees to take root. And we have only considered the plants—imagine what else comes along with this growth! Insects, birds, reptiles, mammals, and more, all thriving on what once was empty rock.

This process of moving from bare rock to a flourishing ecosystem is called primary succession. It describes the succession of species and events that build on one another to create an established, living community (in ecology, this is called a climax community).

Now, imagine that a fire sweeps through our climax community, burning through all of the vegetation. You might think we are back to square one! But in reality, we have an advantage: the soil stays behind. And after the fire, it is thicker and richer than ever before.

Secondary succession…tells us which species colonise a landscape after a major natural disturbance, and the order in which those species arrive.”

Because of this, fast-growing plants are able to colonise the soil much more quickly than the first time around, and a climax community once again takes shape. This process, called secondary succession, is the one that is of interest to us. It tells us which species colonise a landscape after a major natural disturbance (in our example, fire), and the order in which those species arrive.

Now that we understand the concepts of colonisation and succession, we are ready to take our ecological knowledge into the garden.

Most gardens are disturbed ecosystems, transformed by a series of human interventions.”

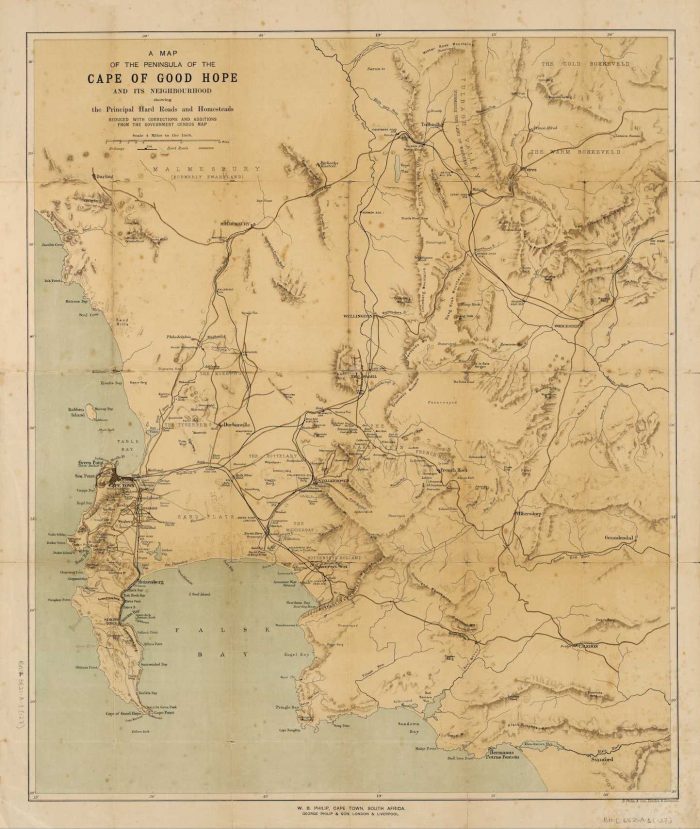

Though it may come as a surprise, my typical suburban garden is actually a disturbed ecosystem. The disturbance was not a fire, like in the previous example, but rather a series of human interventions. 300 years ago, this little patch of earth in the suburbs was not part of a “suburb” at all! Rather than fence lines and homes, this region was characterized by vast expanses of sandy soil, sparsely covered with native shrubs and trees. It sat in the heart of a biome called the Cape Flats Sand Fynbos.

The growing human population within the city of Cape Town took its toll on the land. Heavy ox wagons struggled to travel across the deep sand, and in the early 1800s, authorities introduced alien plant species from Australia in an attempt to stabilize the soil. Though the sand was effectively stabilized, it came at a heavy cost: the original Cape flats sand fynbos ecosystem was overrun with non-native species, and was pushed to the brink of extinction.

In Pinelands, where I stay, thousands of non-native pine trees were also introduced in the late 1800s to control the shifting sands. Over the next 100 years, the area subsequently served as a brick-making business, a camp for the British army, a set of hostels for bubonic plague patients, and, eventually, a suburb of Cape Town.

Who will colonise the land once fynbos is present?”

It isn’t hard to see how human influence has “disturbed” the area—in fact, disturbance seems a mild term for the radical change inflicted on the landscape! My little garden is not a true case of secondary succession; though it is primarily sandy soil, there is some plant growth. But as we slowly clear the alien trees and plants and begin to introduce native vegetation, it will be fascinating to see what non-plant species come back.

Who will colonise the land once fynbos is present? Will new birds arrive? New insects? Which will come first, and pave the way for others? Where will they come from, and what seeds will they carry with them? The questions are expansive and inviting, and for me, learning their answers is one of the most exciting prospects of “re-wilding” a garden.

For those of you who also enjoy these sorts of questions, here are a few more to consider:

- Do you know the “disturbance history” of your garden or city?

- How have you witnessed landscapes changing over your lifetime?

- Where can you see the principles of succession at work?

If you have a succession story to share, leave a comment on this blog or send us an email—we would love to hear it!

Until next time, happy exploring!

Further reading

History of Pinelands: The Garden City of Pinelands, South Africa

Fantastic beginnings of localising our garden. Can’t wait to follow your findings on how this changes who shows up to the party!