I was employed as Ecologist/Research Officer by the Swaziland National Trust Commission (now Eswatini National Trust Commission), the parastatal organisation responsible for the conservation of Eswatini’s cultural and natural resources, from 1986 to 1995. My responsibilities were the research programmes and activities for guiding management of the ENTC’s nature reserves, and to provide information for conservation of the country’s biodiversity. Part of the work that I did was to begin compiling information on the flora and fauna found within the ENTC reserves.

In terms of biodiversity field work, my initial focus was on the grasses, as little information was available at that stage, and this extended to general plant collection, usually focusing on groups of plants which had not been well investigated. At this stage, very little information was digitized, and, in collaboration with the Pretoria Herbarium, I put together the Flora Database for Eswatini, and in the early to mid ’90s created the ENTC website, which made this information available to the public.

After 1995, I continued to work for ENTC on a part time basis as a consultant, maintaining the website, and taking photos for them for publicity purposes. This overlapped with my interest in photography, and when digital cameras became available, I focused on taking photos of the flora for the database/website, rather than collecting specimens.

One of the biggest problems I encountered when trying to compile biodiversity information was the difficulty in finding resources to try and identify plants and animals. Hard copy publications were available, but a small organisation like the ENTC was in no position to budget for the purchase of a broad selection of books and journals. At that stage, online resources were very limited.

In the process of taking photos of the flora, I started getting photos of butterflies and other invertebrates as well. With regard to butterflies and moths, Neville Duke and Chuck Saunders did a lot of collecting in the country, but the only information I had available was hand written lists of species recorded from Malolotja and Mlawula Nature Reserves, which gave me a starting point of 222 species of butterflies recorded in Eswatini.

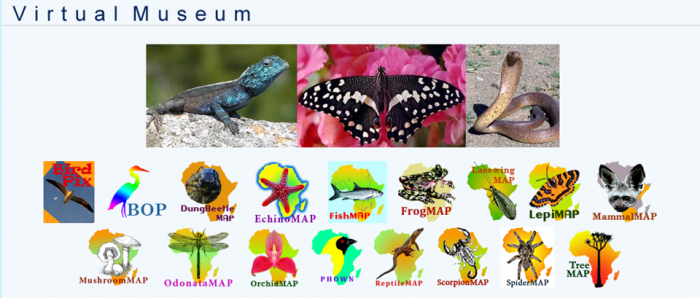

In 2008, I discovered the UCT-ADU Virtual Museum as a means of getting photos identified, and over then next few years, I was able to get photos of a number of species of butterflies. The Virtual Museum provided the resources for me to be able to compile an updated illustrated checklist of the butterflies including about 280 species: Eswatini Butterflies Checklist, August 2013

As the Virtual Museum grew, I expanded my focus, including other groups of fauna where the expertise was available for identifications. From around 2011, my focus included the dragonflies and damselflies. Initial information on species possibly occurring in Swaziland was available from Dragonflies and Damselflies of South Africa by Michael J. Samways, and I found a southern African checklist online, published by the Department of Entomology & Arachnology of the Durban Natural Science Museum. Combining this with the photo records I was able to obtain, and by using the resources of the Virtual Museum, I was able to put together a provisional checklist of Eswatini’s Odonata in 2012. This has been upgraded and additional information included, and as at 2018, includes 82 species: Eswatini Odonata Checklist, 2018

In 2016, one of my contracts was the biodiversity information component of the SNPAS project (Strengthening National Protected Areas Systems Project). My task was to compile a data set of all available existing records of flora and fauna recorded in Eswatini. I have been working on making this information available via the ENTC website, and am developing the Biodiversity Explorer component of the website to make this information more accessible to non-scientists.

In 2016, one of my contracts was the biodiversity information component of the SNPAS project (Strengthening National Protected Areas Systems Project). My task was to compile a data set of all available existing records of flora and fauna recorded in Eswatini. I have been working on making this information available via the ENTC website, and am developing the Biodiversity Explorer component of the website to make this information more accessible to non-scientists.

In early 2017, I started focusing on getting photos of the moths, and this has coincided with more and more information being available online to assist with identifications, as well as updates of the taxonomy of various groups of moths. Prior to this, existing available information included a list of about 800 species of moths. Since then, I have been able to obtain some of the record information for previous collections, in particular, those collected by Neville Duke in the 1980’s/90’s, but as most of his collection, housed in the Ditsong Museum, has not yet been digitized, there is still a huge amount of information not yet easily available.

Over the last couple of years, in collaboration with various people, I have been able to put together a provisional checklist, which currently includes over 1300 species. Much work is still needed on this, and many photos still require identifications, so it is expected that the checklist will have many additions — Eswatini Provisional Moths Checklist — Special thanks go to Quartus Grobler for all the time and effort he has put into helping with identification of moth photos.

In collaboration with Mervyn Mansell, I am also currently working on a similar illustrated checklist for the Neuroptera, and this should be available soon. I am currently working with the ENTC on an upgrade of the website, and once we have the new format in place, I will be upgrading and updating the biodiversity information available on the website. So much of what I have been able to put together has been dependent on collaboration with organisations and individuals, both scientists and “citizen scientists”. In spite of all the photos I’ve already taken, I am still getting records of new species for Eswatini, an indication of how much work is still to be done.

What are you still hoping to achieve? This might be in terms of species, coverage, targets …

In Eswatini, most of the vertebrate species of fauna found in the country have been documented, but this doesn’t apply to many groups of invertebrates. There will still be many years of work to document this diversity, and I hope to continue to collaborate with organisations such as the Animal Demography Unit to continue to further our knowledge of Eswatini’s fauna and flora, and to make this information available and accessible.

What do you see as the role which citizen science plays in biodiversity conservation? What is the link?

I believe that citizen science is an invaluable approach for documenting biodiversity. Current technology allows for more and more people to be directly involved, making it possible to obtain a huge amount of information on species presence and distributions, far more than could be obtained by scientists without this help. Citizen science also raises awareness of the richness of our biodiversity, and can only help in the long term conservation of our flora and fauna.